National pasttime losing its appeal for kids

Mar 31, 2011, 4:17 PM | Updated: 5:18 pm

NEW YORK — Major League Baseball has begun its 2011 season with a problem, according to The Wall Street Journal.

The number of kids aged 7 to 17 playing baseball fell 24 percent from 2000 to 2009, reports the National Sporting Goods Association, an industry trade group. Despite growing concerns about the long-term effects of concussions, participation in youth tackle football has soared 21% over the same time span, while ice hockey jumped 38%.

The Sporting Goods Manufacturing Association, another industry trade group, said baseball participation fell 12.7% for the overall population.

“I like baseball, but it’s just too slow for me,” said 13-year-old Hank Crone — grandson of a major leaguer and son of a top scout for the Detroit Tigers.

With 11.5 million players of all ages in the U.S., baseball remains the fourth-most-popular team sport, trailing basketball, soccer and softball. But over the last 16 years, numbers for Little League Baseball, which accounts for about two-thirds of the country’s youth play, have been steadily dropping. And there are signs the pace is accelerating.

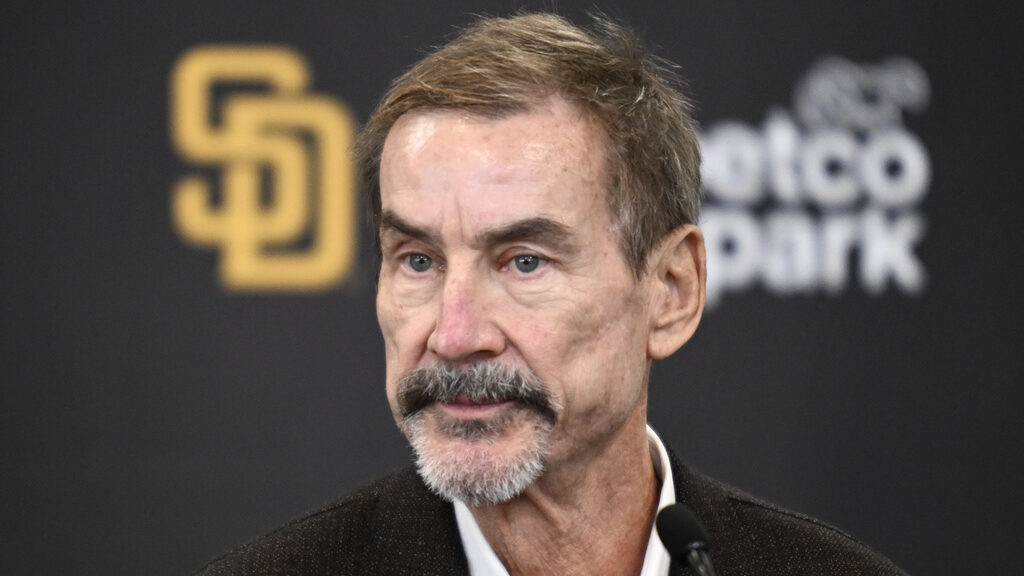

“The days of kids being born with a glove next to their ear in the crib and boys playing catch in the backyard by age three, those are over,” said Len Coleman, the former president of the National League.

Coleman, who counts Hall of Famers Hank Aaron and Frank Robinson as close friends, said he watched his son, now 23, drop baseball as a teenager for soccer—the sport he starred in at Georgetown University.

“I even tried to keep him interested by having him catch so he’d be involved in every play,” Coleman said.

Tim Brosnan, an executive vice-president for Major League Baseball, said the recent gloomy studies have prompted the league to order up its own research, which is ongoing, and to review the league’s efforts to grow the game.

Since 1989, baseball has spent more than $50 million building and renovating fields and creating baseball leagues, especially in urban areas where kids have been abandoning the sport. It has also opened youth training academies in California and Texas to teach all aspects of the game—even umpiring.

“We know if you play as a kid you over-index in your propensity to become a fan,” Brosnan said. “That’s our core right there, so any decline in it is going to get our absolute and full attention.”

There hasn’t been any definitive research on why baseball is losing ground. Anecdotally, parents say it has to do with the game’s languid pace—and the fact that other sports do a better job forcing kids to stay alert.

Coleman, the former National League president, said baseball’s only hope may be to make some radical changes in youth and high school play.

His idea: eliminate the walk. Walks slow the game down, he said, and also rob the best players of opportunities to hit because opposing pitchers get orders from their coaches to walk the other teams’ best players.

“Give the batter three strikes and tell the pitcher he’s got to throw the ball over the plate,” Coleman said. “That ought to liven things up.”