A bookie, a bet, a basketball player: The scandal that rocked ASU

Dec 18, 2018, 7:37 AM | Updated: 7:41 am

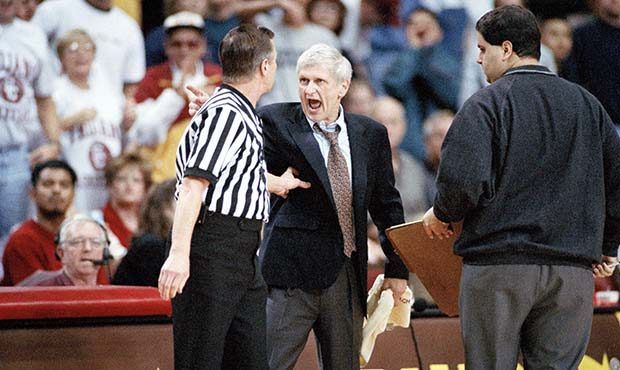

Arizona State head coach Bill Frieder vehemently argues with an unidentified official over a call against Arizona State during first-half action at the Los Angeles Sports Arena on Saturday, Jan. 18, 1997. (AP Photo/Chris Pizzello)

(AP Photo/Chris Pizzello)

PHOENIX – Through renovation and coaching changes, the ground floor of the Ed and Nadine Carson Student-Athlete Center at Arizona State has withstood the test of time.

The museum is designed to chronicle proud moments in ASU athletics history, highlighting alumni such as Houston Rockets guard James Harden and former San Francisco Giants outfielder Barry Bonds.

But hidden among the numerous plaques and glass cases stocked with memorabilia lies history buried in the shadows of infamy. Twenty-five years ago, the Arizona State men’s basketball program was at the center of a point-shaving scandal, one that has triggered new discussion in light of the Supreme Court’s decision in May to clear the way for states to legalize sports betting.

“If gambling on colleges is (allowed) in 20 or 30 states, there is probably a 100 percent chance of a point-shaving scandal at some school,” Tom McMillan, CEO of LEAD1, an organization for athletic directors, said in April at a conference of the Sports Lawyers Association.

Under coach Bill Frieder, the 1993-94 men’s basketball team was poised for a spot in the NCAA Tournament, led by senior guard Stevin “Hedake” Smith, a potential first-round draft pick.

Smith entered the season as the leading returning scorer in the Pacific-10 Conference. As good a scorer as Smith was, his betting luck wasn’t.

Accruing debt of at least $10,000 owed to ASU student and campus bookmaker Benny Silman, Smith didn’t need much persuading when an opportunity to cover his losses presented itself.

“We agreed that I could repay my debt to him by fixing the basketball game,” Smith said in court documents from his plea agreement. “In return for fixing the game, Silman agreed to pay me about $20,000 per game.”

In sports betting, odds are determined based upon the likelihood a team or individual competitor will win against an opponent. From there, a point spread is established to gauge by how large a margin a bookmaker believes one team can win, for betting purposes.

Point-shaving requires one team, favorite or underdog, to intentionally alter the outcome of a game. Smith’s case involved ASU winning games by fewer points in which it was heavily favored.

The introduction of entrepreneur Joseph Gagliano, 25, into the fold enabled Silman’s operation to reach new heights.

“I remember distinctly (Silman) calling me back in Chicago,” Gagliano told Cronkite News. “‘Hey Joe, I got a fix for you.’

“I played it off like I understood what he was saying and then finally, he spelled out the letters.”

F-I-X.

Buckets for bucks

Any good surgeon can vouch for the importance of being meticulous. From sanitizing to preparation to execution, one mistake can impact an entire procedure. The same goes for fixing a basketball game.

After examining the Sun Devils’ schedule, Gagliano decided on a Jan. 27 matchup with Oregon State. The game was in Tempe, just three days before the Super Bowl, and ASU was favored by 14½ points.

Under the instruction of Silman and Gagliano, Smith was to provide a six-point victory. Bets would be made on ASU to win while failing to cover the spread, meaning both the Sun Devils and bettors could come out on top.

Gagliano arrived in Las Vegas on Thursday with $500,000 to wager, enlisting the help of his father and two others to unload the money before tipoff, he said.

The process was nothing short of arduous.

Utilizing more than 30 sportsbooks, the group bet in increments of $9,900 per ticket to avoid filling out a Currency Transaction Report – a red flag to the Internal Revenue Service that allows the IRS to examine the tax returns of a customer – but more importantly, to prevent betting lines from shifting.

“Back then in that day, there were many hole-in-the wall sportsbooks out there that are certainly not there now because they’re all corporate,” Gagliano said. “There was certainly a lot of adrenaline, a lot of planning.”

Aside from betting $500,000 in one afternoon, much of the planning revolved around Smith’s play, though even he couldn’t plan for a better-timed performance.

Defensively, Smith intentionally conceded additional space to shooters, he later acknowledged, allowing the Beavers to score often and keep the game interesting. He attributed his own offensive prowess as the key to knowing how much room to allow.

Normally that would draw the wrong kind of attention to him, but it was largely overlooked as the senior scored a career-high 39 points, draining 10 3-point shots. ASU covered with a six-point win.

The fix was back in play against Oregon that Saturday. With betting that exceeded $1 million this time, the Sun Devils won by six in consecutive games, successfully fixing both contests.

In total, about $3.3 million was won in three days, with profits exceeding $2.5 million in cash, Gagliano wrote in his book, “No Grey Areas.”

“It was really easier to blend in because there was so much activity in the sportsbook with the Super Bowl going on that weekend,” he said.

Purple reign on the parade

“People were starting to connect the dots. Dots I didn’t want connected, especially from the types of people connecting them,” Gagliano said in his book.

With gamblers pleased about three wins and being $5.1 million up, ASU was falling out of NCAA Tournament contention with one final game on the agenda: Washington.

Confidence shifted to doubt and Gagliano wasn’t eager to bet. When he started making his rounds through various sportsbooks, his uneasiness grew.

Days earlier against USC, the $2.5 million he placed on the Trojans had a dramatic impact on the point spread, dropping it from 9½ points to 5.

Against Washington, he couldn’t help but notice students in Sun Devil apparel lined up across betting windows down the Las Vegas Strip, plummeting a 12-point spread favoring ASU down to three on the same day.

Word had spread on campus about the fix.

In fact, this game generated so much action that according to the Las Vegas Review-Journal, Jimmy Vaccaro, a former sportsbook director at the Mirage, notified the Nevada Gaming Control Board.

The March 5 meeting between ASU and Washington remains the largest one-day movement on a betting line, Gagliano said.

“It was just too obvious,” said Jay Kornegay, vice president of Las Vegas Hotel & Casino SuperBook. “When someone wants to make a bet and they don’t care what the line is, that’s a red flag.”

Kornegay noted that the fix might not have been discovered if bets were not taken on ASU in the Washington game.

An 18-point win for the Sun Devils far exceeded the original point spread, emptying the pockets of those who bet against ASU.

But the losses sustained were incomparable to the ensuing federal investigation.

Amid the initial allegations swirling around the program, Frieder remained accessible and open, but the gravity of the situation was evident, taking a toll on the coach. Arizona Republic reporter Kent Somers recalls Frieder reaching out late at night to discuss the matter.

“He (Frieder) talked about it several times in his weekly press conference right after the news broke,” Somers said. “He went on sort of this long, bizarre monologue.”

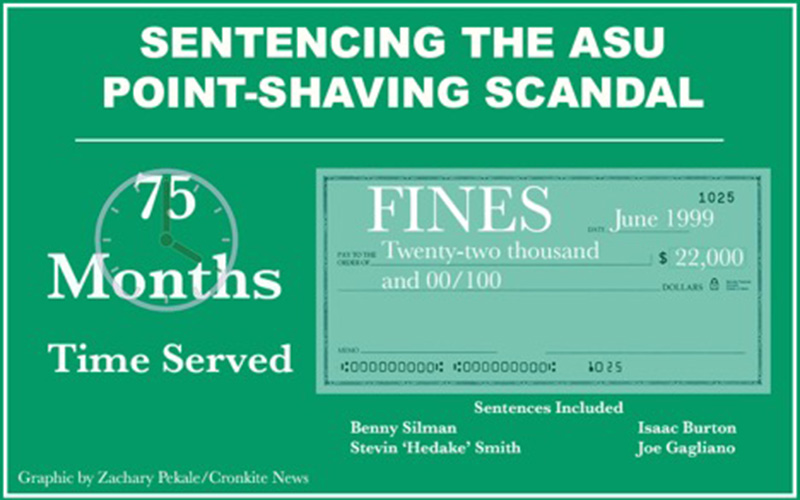

But within a few years, allegations turned into trials, culminating in the sentencing of Smith, Silman and others.

After sentencing fines totaled $22,000 and 75 months were served. (Graphic by Zachary Pekale/Cronkite News)

Smith, once primed for a promising NBA career, went undrafted in 1994, with his lone chance coming in the form of two 10-day contracts with the Dallas Mavericks in 1997 before his sentencing, totaling one year in prison, three years probation and a $8,000 fine.

By that time, Frieder had left ASU. He did not coach again.

Understanding risks

In the 25 years since Arizona State was at the epicenter of a huge point-shaving scandal, sports betting continues to be a hot button topic, especially after the Supreme Court decision in March that cleared the way for states to legalize sports betting, thereby making gambling more accessible.

And many student-athletes continuing to have an interest in betting overall. The good news for the NCAA is their involvement has decreased. A study conducted by the NCAA concluded the rate of male athletes who gamble for money dipped 11 percentage points from 2008 to 2016.

However, among those who gamble, 24 percent of men and 5 percent of women wagered specifically on sports, a violation of NCAA bylaws.

The risks linger.

Per the NCAA, in 2016, 11 percent of Division I football players and 5 percent of men’s basketball players reported betting on a college game in their sport not involving their team.

Among the general population, gambling and sports wagering remain on the rise.

On November 17, Hollywood Casino at Penn National Race Course opened a fully operational sportsbook, the first in the state of Pennsylvania.

The casino filed an application with the Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board and eventually paired with joint-venture partner William Hill, allowing Hollywood Casino to launch its sportsbook.

“We couldn’t have gotten this done without (the Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board). They helped us expedite the application,” said Fred Lipkin, vice president of marketing at Hollywood Casino. “There are a lot of people who like to wager on sports and used to have to make that trip all the way to Las Vegas, and now with the convenience of having it here in south central Pennsylvania, we had a lot of buzz.”

Asked about the preventative measures necessary to prevent circumstances relatable to Arizona State’s scandal, Lipkin declined comment.

Some experts fear college players are vulnerable to point-shaving opportunities because of NCAA rules that limit their compensation.

Six states have legalized sports gambling and 21 others plus the District of Columbia are looking into it since the Supreme Court ruling. Arizona has not yet, in part because of the Arizona Tribal-State Gaming Compact between the state and Native American communities complicates the issue.

At the least, the ruling has the NCAA’s attention, and an ASU basketball season 25 years ago serves as a reminder of what could unfold.